Animals, birds, and insects write diaries with their feet and we can read them to determine who wrote them. Indigenous Australians relied upon their ability to read the stories in the sand told by footprints and scats to direct them toward food sources.

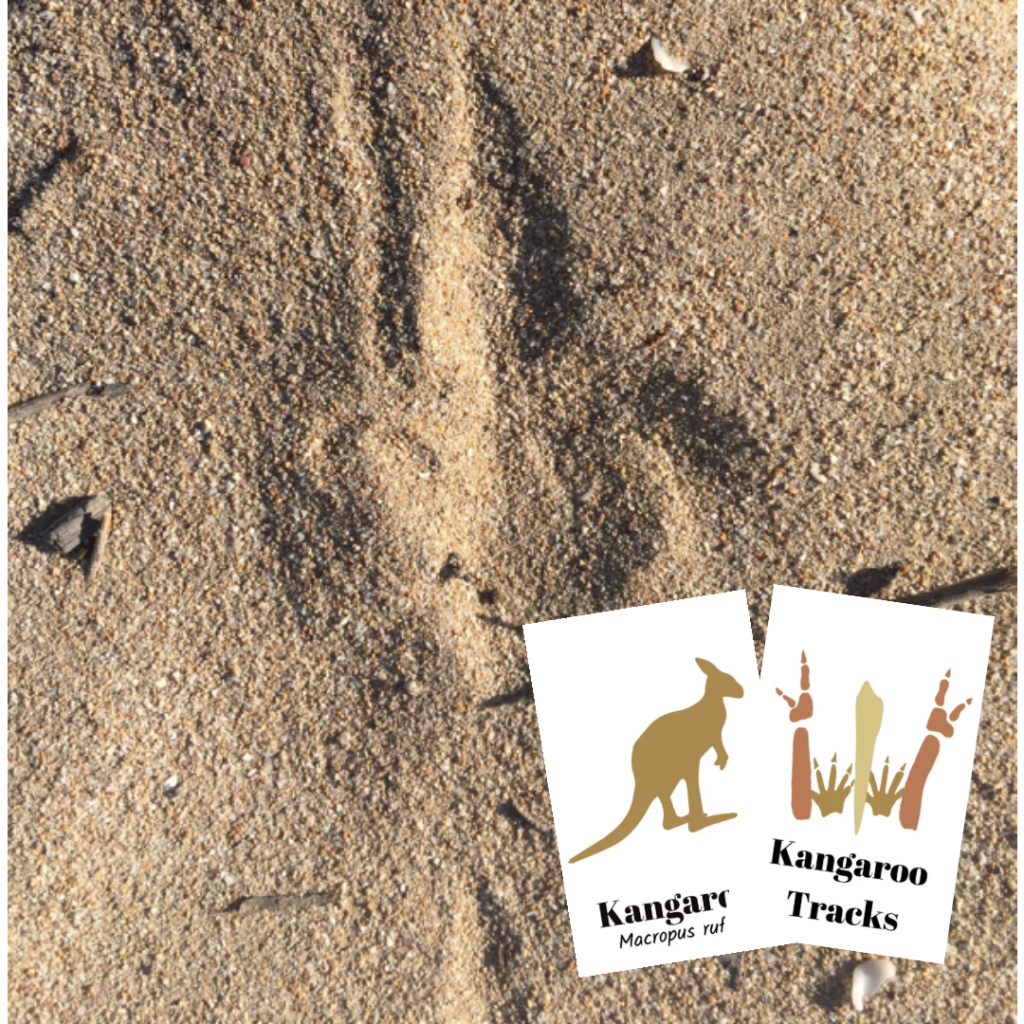

It is challenging to distinguish tracks at first, but once the skill is mastered they are a valuable source of information. Trails don’t last very long as they’re either smudged, or the wind and rain erase the evidence of animals in the area.

Tracks will tell us if the animal was running, leaping, hopping, or walking by examining their gait. The size of the track will also give us an idea of how large the animal is. We may notice that the creature stopped to change direction. We may wonder why. Or as we’re following the track, we may come upon an obstacle and we can investigate to find out how the creature overcame it. The intriguing thing about tracking is that we don’t know what we’ll find at the trail’s end. A burrow, perhaps?

Droppings, dung, faeces, poo whatever you call it, is full of information about the creature who dropped it if you can read it. The study of scats known as scatology aids in the study of animal populations, diets, genetics, and behaviours. The word ‘scat’ comes from the Greek word ‘skat’ meaning excrement or faeces.

Examining scats is a smelly, messy business! It can be seriously GROSS but the scientist in me is curious enough to overlook the obvious to find the secrets in the mess. A scat can reveal the animal species when it had passed by, and what its diet consists of. It can also tell us how much it weighs, how old it is, and sometimes if it is a male or female. Amazing right? All this information from poop!

Foxes and wombats use their scats to mark their territory. When we wonder about the ownership of a burrow or tree hollow, we can search for scats to answer our questions. Have you happened upon animal trails during outdoor adventures? Did you notice scats on these trails? Now you can practice the skill of scatology and know the stories of the pathway.

Occasionally, scats are difficult to identify when species like the kangaroo and wallaby are similar in shape, size, and diet. But the scats of herbivores and carnivores can be told apart if the scat is fresh by its odour. Herbivore scats smell like humus while carnivore scats are more offensive, mainly if the owner ate carrion.

Herbivore scats can be green, brown, or black depending on the season. Older scats look weathered and paler. They are often in the shape of pellets and plant particles can be seen.

Carnivore scats are cylindrical and sometimes pointed at one end. Bone and hair fragments are visible.

Insectivore and omnivore scats are less foul-smelling than carnivore scats and have distinct odours. Fragments of plants and or insects are visible when the scat is broken apart. Particles of soil or bark in the scats are evidence of the type of foraging.

Are you inspired to unlock the mysteries of animal tracks and scats? I hope so! We have some cool resources that will make you a professional tracker.

Table of Contents

Go Walkabout:

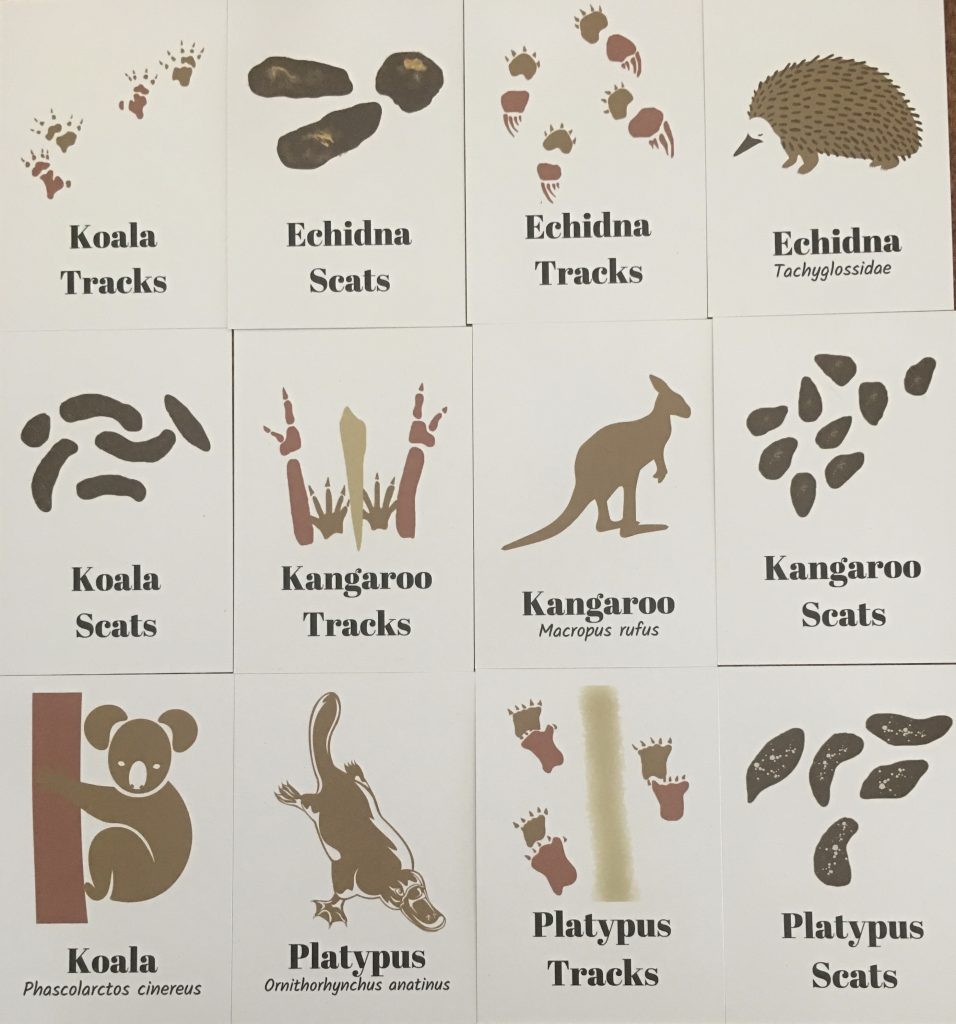

Step into your detective shoes and explore the outdoors for animal traces. They can be tracks, scats, nests, and burrows. Use our Animal Track and Scat Cards to identify the writings in the sand. There is a PDF version, but we are ecstatic to announce we have added a physical set of Aussie Animal Track and Scat Cards for you to take on outdoor detective adventures. But be quick as we have a limited supply available for immediate shipment.

What can you tell about the creature who left the traces behind? Where was it coming from and where is it going?

In what kind of habitat is the animal or bird living and how many more tracks can you find? How many creatures of the same species live in this area?

Measure the tracks and sketch them into your nature journal along with your observations.

WARNING: Animals carry worms and parasites that are harmful to humans. Please investigate scats with great care and hygiene under adult supervision. Always wear gloves.

Examine the scats you find with tools like a spatula or stick, and gloves. If the pellets are warm and steaming, the creature is close. Are the scat’s soft and fresh? It may be a day or so old. If the pellets are light and dry, they may be a week or more old.

What shape are the scats? Are they oval, round, or square? What is the approximate width of the scat? Measure at the widest part. If there is more than one, measure the scats to determine the average size. Break the scat apart and probe inside. Is the creature a herbivore, carnivore, omnivore, or insectivore? Then use this information along with animal distribution maps and a scat field guide like Tracks, Scats and Other Traces by Barbara Triggs to find the owner.

Get Creative:

Create a sand pad in the pathway of animals who frequent the area you explore by loosening the soil, dampening it with water, and gently packing it down again. Patiently visit your sand pad often to see if an animal or bird has passed by. Identify the tracks.

Visit a playground where children have played. Follow the tracks of one to discover where they came from, if they walked or ran, and the direction they were going.

What kind of tracks would your hands and feet make in mud? Find out!

Read the stories of the animal tracks and scats you found and share them with a friend.

Make play dough and encourage your pet to create a paw print for you.

Watch different birds walk in your yard or park, follow them, investigate the traces, and sketch them in your nature journal.

Research:

Explore Aboriginal Art Symbols known as Iconography and how they tell stories using animal tracks.

Become an Echidna CSI and track Echidnas in your area. Take photos, and videos, and mail away scats to aid in echidna research and conservation. Learn more and download the App HERE.

Help scientists map wombats with the WomSat Project.

Read:

Who Did That 2 by Jill B. Bruce

Jo has created a Book Pack for Who Did That 2 by Jill B. Bruce. This Book Pack is designed for Upper Primary (8-12), and some activities will suit older High School Students (13+). Key Learning Areas are English, Math, Science, Geography and Art.

Explore Etymology, the origin of words, and how they have changed with time. Introduce animal common and Latin names with interesting stories. For instance, The ‘kangaroo’ comes from the Guugu Yimidhirr people sharing the word ‘gangurru’ with James Cook in 1770.

Research the reasoning behind using Latin to name animals, then dive into the understanding of root words of the English language. For example, the root word ‘macro’ means big or large and the word ‘pus’ means ‘of the foot’ so Macropus means ‘large foot.’ Play with Greek\Latin Root Memory Cards to build fluency and understanding of this concept. Use Word Bank Cards to collect words with Greek and Latin roots.

Using the information provided in Who Did That 2, create an animal size and weight graph. Practice reading and interpreting data for each animal, and create distribution maps with clear acetate and permanent markers.

Investigate how the science of DNA can help scientists learn more about animals and how school students are helping by collecting koala scats for research. Examine scats to find out who left that behind. Then write your findings in a Scat Observation Activity Worksheet.

Create a printed track collage. Research the Aboriginal symbols for animal tracks and design your own piece of art.

This is a great resource for introducing primary-aged children to reading mysteries on pathways.

Who Did That 1 by Jill B. Bruce Book Pack coming soon…

Reading Tracks by Margaret James

Animal Tracks by Arthur Dorros | Read Aloud

Watch:

Animal Track Detective by SciShow Kids

How to Track Animals by Ranger Zak Show

Poem:

Sleeping Out by Jane Routh No wind in the pines — I didn’t believe the forecast yet pulled my bivvy bag part-way under the awning where I could still see the stars. When I woke, it had snowed a light coverlet on me; more — say two inches — on the ground and melting already so the tracks of a creature which had stalked round my unknowing body were hard to decipher, their indents collapsing: four-toed I thought — a fox’s most likely or were the prints wider, the tread of a wildcat? Some moist muzzle had leaned close by my head breathing my breath and eavesdropping dreams while taking my measure along and back then around — much the same as the way I might sniff at a spraint or track deer-slots to a lair, as if I might bed down too, try out how the world feels from there.